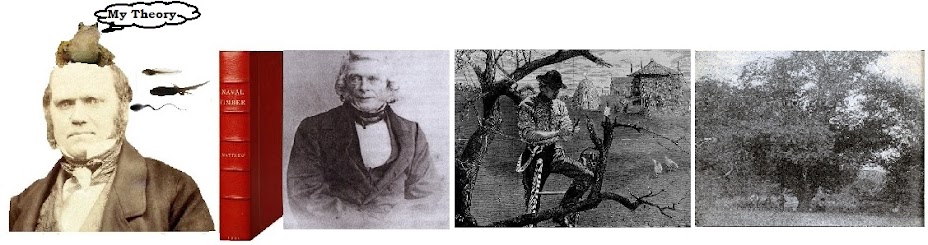

"Darwin" - authored by Jonathan Howard and published in 1982 by Oxford University Press paperback has so far disseminated two myths on page 1 alone (see links at the end of this blog post) .

"Darwin" - authored by Jonathan Howard and published in 1982 by Oxford University Press paperback has so far disseminated two myths on page 1 alone (see links at the end of this blog post) . In three blog posts on Darwin myths found so far in Howard's book, I have not yet progressed beyond page 1. The third myth on page 1 is the myth that Darwin was an original thinker and his work was highly idiosyncratic.

Howard (1882, p. 1) writes: 'Darwin wrote a series of personal notebooks which record the earliest developments of the theory of evolution in the most idiosyncratic and fascinating detail.'

This is the sort of thing that has steered scholars away from the actual facts. By way of example, Darwin's private unpublished essay of 1844 replicated Patrick Matthew's (1831) highly original and powerful artificial selection versus natural selection explanatory analogy of differences between trees raised by main in nurseries and those naturally selected in the wild.

'Man's interference, by preventing this natural process of selection among plants, independent of the wider range of circumstances to which he introduces them, has increased the differences in varieties particularly in the more domesticated kinds...'

New Data Demands Paradigm Shift: https://t.co/LMpbVPMAh6 pic.twitter.com/P5IDcp4ry4

— Dr Mike Sutton (@Dysology) July 10, 2016

Darwin wrote (1844 - private essa) wrote:

Taking out the trees example, Darwin (1859), in opening words of Chapter One of 'The Origin of Species' Darwin again used Matthew's powerful artificial selection versus natural selection explanatory analogy of differences - without citing Matthew.'In the case of forest trees raised in nurseries, which vary more than the same trees do in their aboriginal forests, the cause would seem to lie in their not having to struggle against other trees and weeds, which in their natural state doubtless would limit the conditions of their existence…"

What Matthew first originated in 1831 wrote was replicated by several naturalists who followed in his footsteps. Beginning with Matthew, the originator, it is useful to examine who wrote what on this precise analogy and when.

1. ‘Matthew (1831 pages. 307-308 )) wrote

‘The use of the infinite seedling varieties in the families of plants, even in those in a state of nature, differing in luxuriance of growth and local adaptation, seems to be to give one individual (the strongest best circumstance-suited) superiority over others of its kind around, that it may, by overtopping and smothering them, procure room for full extension, and thus affording, at the same time, a continual selection of the strongest, best circumstance suited for reproduction. Man’s interference, by preventing this natural process of selection among plants, independent of the wider range of circumstances to which he introduces them, has increased the difference in varieties, particularly in the more domesticated kinds; and even in man himself, the greater uniformity, and more general vigour among savage tribes, is referrible to nearly similar selecting law - the weaker individual sinking under the ill treatment of the stronger, or under the common hardship.'

Matthew (1831) pages.107-108

'... in timber trees the opposite course has been pursued. The large growing varieties being so long of coming to produce seed, that many plantations are cut down before they reach this maturity, the small growing and weakly varieties, known by early and extreme seeding, have been continually selected as reproductive stock, from the ease and conveniency with which their seed could be procured; and the husks of several kinds of these invariably kiln-dried, in order that the seeds might be the more easily extracted. May we, then, wonder that our plantations are occupied by a sickly short-lived puny race, incapable of supporting existence in situations where their own kind had formerly flourished—particularly evinced in the genus Pinus,more particularly in the species Scots Fir; so much inferior to those of Nature's own rearing, where only the stronger, more hardy, soil-suited varieties can struggle forward to maturity and reproduction?

We say that the rural economist should pay as much regard to the breed or particular variety of his forest trees, as he does to that of his live stock of horses, cows, and sheep. That nurserymen should attest the variety of their timber plants, sowing no seeds but those gathered from the largest, most healthy, and luxuriant growing trees..'

Matthew (1831) page 3:

There are several valuable varieties of apple trees of acute branch angle, which do not throw up the bark of the breeks; this either occasions the branches to split down when loaded with fruit, or if they escape this for a few years, the confined bark becomes putrid and produces canker which generally ruins the tree. We have remedied this by a little attention in assisting the rising of the bark with the knife. Nature must not be charged with the malformation of these varieties; at least had she formed them, as soon as she saw her error she would have blotted out her work.'

Matthew (1831) pages 261-263

' We ask if even the fact of these unnaturally tender varieties (obtained by long continued selection, probably assisted by culture, soil and climate, and which, without the cherishing of man, would soon disappear)..'

Matthew (1831) page 67:

'It is also found that the uniformity in each kind of wild growing plants called species may be broken down by art or culture and that when once a breach is made, there is almost no limit to disorder, the mele that ensues being nearly incapable of reduction.'

Matthew (1831) page 387: 'As far back as history reaches, man had already had considerable influence, and had made encroachments upon his fellow denizens, probably occasioning the destruction of many species, and the production and continuation of a number of varieties or even species, which he found more suited to supply his wants, but which from the infirmity of their condition—not having undergone selection by the law of nature, of which we have spoken cannot maintain their ground without his culture and protection.'

Matthew (1831) Here Matthew refers to crab apple trees – which are likely the closest to the original, and most hardy of the apple species. He crosses his unique heretical discovery of natural selection with is unique use of the Artificial Selection versus Natural Selection Analogy with his seditious Chartist libertarian social reform politics to propose a bio-social explanation for why it is bad for human stock (as a national or regional variety) and bad for human society if there is not free crossing in complex human society as there is in societies which may be closer to 'nature'. He writes on page 366:

‘It is an eastern proverb, that no king is many removes from a shepherd. Most conquerors and founders of dynasties have followed the plough or the flock. Nobility, to be in the highest perfection, like the finer varieties of fruits, independent of having its vigour excited by regular married alliance with wilder stocks, would require stated complete renovation, by selection anew from among the purest crab.’

Matthew (1831) Pages 381 - 382. It is here that Matthew, heretically, hands "God" his redundancy notice. To do so, he uses the analogy in question to demonstrate (provide what he believes is evidential "proof") that living matter has the plastic (malleable) quality necessary to create new species by way of their diverging from ancestral varieties with which they would thereafter be incapable of breeding :

' We are therefore led to admit, either of a repeated miraculous creation; or of a power of change, under a change of circumstances, to belong to living organized matter, or rather to the congeries of inferior life, which appears to form superior. The derangements and changes in organized existence, induced by a change of circumstance from the interference of man, affording us proof of the plastic quality of superior life, and the likelihood that circumstances have been very different in the different epochs, though steady in each, tend to heighten the

probability of the latter theory.'

probability of the latter theory.'

Mudie (1832) Page 368:

‘If we are to observe nature, therefore, we must go to the wilds, because, in all cultivated productions, there are secondary characters produced by the artificial treatment, and we have no means of observing a distinction between these, and those which the same individual would have displayed, had it been left to a completely natural state. The longer that the race has been under the domestication and culture, the changes are of course the greater. So much is that the case that in very many both of the plants and animals that have been in a state of domestication since the earliest times of which we have any record, we know nothing with certainty about the parent races in their wild state. As to the species, or if you will the genus we can be certain. The domestic horse has not been cultivated out of an animal with cloven hoofs and horns; and the domestic sheep has never been bred out of any of the ox tribe. So also wheat and barley have not been cultivated out of any species of pulse, neither have Windsor beans at any time been grasses. But within some such limits as these our certain information lies; and for aught we know the parent race may, in its wild state, be before our eyes every day and yet we may not have the means of knowing that it is so. The breeding artificially has been going on for at least three thousand years…’

Mudie (1832) Page 369-370

‘But there is another difficulty. When great changes are made on the surface of a country, as when forests are changed into open land, and marshes into corn fields, or any other change that is considerable, the changes of the climate must correspond; and as the wild productions are very much affected by that, they must also undergo changes; and these changes may in time amount to the entire extinction of some of the old tribes, both of plants and of animals, the modification of others to the full extent that the hereditary specific characters admit, and the introduction of not varieties only but of species altogether new.

That not only may but must have been the case. The productions of soils and climates are as varied as these are; and when a change takes place in either of these, if the living productions cannot alter their habits so as to accommodate themselves to the change there is no alternative, but they must perish.’

Mudie (1832) seemed to be recommending that humans engage in trying to approximate a kind of natural process of selection (370-371):

“Cultivation itself will deteriorate, and in time destroy races, if the same race and the same mode of culture be pursued amid general change. Our own times are times of very rapid change, and, upon the whole, of improvement; we dare not, without the certainty of their falling off, continue the same stock and the same seed corn, season after season, and age after age, as was done by our forefathers. The general change of the country, must have change and not mere succession, in that which we cultivate; and thus we must cross the breeds of our animals, and remove the seeds and plants of our vegetables from district to district. There is something of the same kind in human beings..”

3. Lyell (1832, p, 56) , Matthew's Forfarshire neighbor and Darwin's great friend and geological mentor, wrote:

'…we have no data as yet to warrant the conclusion that a single permanent hybrid race has ever been formed even in gardens by the intermarriage of two allied species brought from distant habitations. Until some fact of this kind is fairly established, and a new species capable of perpetuating itself in a state of perfect independence of man, can be pointed out, we think it reasonable to call in question entirely this hypothetical source of new species. That varieties do sometimes spring up from cross breeds, in a natural way, can hardly be doubted, but they probably die out even more rapidly than races propagated by grafts or layers.'

3. Low (1844) wrote:

‘The Wild Pine attains its greatest perfection of growth and form in the colder countries, and on the older rock formations. It is in its native regions of granite, gneiss and the allied deposits, that it grows in extended forests over hundreds of leagues, overpowering the less robust species. When transplanted to the lower plains and subjected to culture, it loses so much of the aspect and characters of the noble original, as scarcely to appear the same. No change can be greater to the habits of a plant than the transportation of this child of the mountain to the shelter and cultivated soil of the nursery; and when the seeds of these cultivated trees are collected and sown again, the progeny diverges more and more from the parent type. Hence one of the reasons why so many worthless plantations of pine appear in the plains of England and Scotland, and why so much discredit has become attached to the culture of the species.’

4. Darwin (1844 – unpublished essay) wrote

‘In the case of forest trees raised in nurseries, which vary more than the same trees do in their aboriginal forests, the cause would seem to lie in their not having to struggle against other trees and weeds, which in their natural state doubtless would limit the conditions of their existence…’

5. Wallace (1858 Ternate paper) wrote

‘…those that prolong their existence can only be the most perfect in health and vigour – those who are best able to obtain food regularly, and avoid their numerous enemies. It is, as we commenced by remarking, “a struggle for existence,” in which the weakest and least perfectly organized must always succumb.’ [And]: ‘We see, then, that no inferences as to varieties in a state of nature can be deduced from the observation of those occurring among domestic animals. The two are so much opposed to each other in every circumstance of their existence, that what applies to the one is almost sure not to apply to the other. Domestic animals are abnormal, irregular, artificial; they are subject to varieties which never occur and never can occur in a state of nature: their very existence depends altogether on human care; so far are many of them removed from that just proportion of faculties, that true balance of organization, by means of which alone an animal left to its own resources can preserve its existence and continue its race.’

"When we look to the individuals of the same variety or sub-variety of our older cultivated plants and animals, one of the first points which strikes us is, that they generally differ more from each other than do the individuals of any one species or variety in a state of nature.”

"Man selects only for his own good; Nature only for that of the being which she tends. Every selected character is fully exercised by her; and the being is placed under well-suited conditions of life. Man keeps the natives of many climates in the same country; he seldom exercises each selected character in some peculiar and fitting manner; he feeds a long and a short beaked pigeon on the same food; he does not exercise a long-backed or long-legged quadruped in any peculiar manner; he exposes sheep with long and short wool to the same climate. He does not allow the most vigorous males to struggle for the females. He does not rigidly destroy all inferior animals, but protects during each varying season, as far as lies in his power, all his productions. He often begins his selection by some half-monstrous form; or at least by some modification prominent enough to catch his eye, or to be plainly useful to him. Under nature, the slightest difference of structure or constitution may well turn the nicely-balanced scale in the struggle for life, and so be preserved. How fleeting are the wishes and efforts of man! how short his time! and consequently how poor will his products be, compared with those accumulated by nature during whole geological periods. Can we wonder, then, that nature's productions should be far 'truer' in character than man's productions; that they should be infinitely better adapted to the most complex conditions of life, and should plainly bear the stamp of far higher workmanship?'

7. Darwin 1868 wrote (misspelling Matthew's name) : "Our common forest trees are very variable, as may be seen in every extensive nursery-ground; but as they are not valued as fruit trees, and as they seed late in life, no selection has been applied to them; consequently, as Mr Patrick Matthew remarks, they have not yielded different races…" The historian and anthropologist Loren Eiseley saw Darwin's use of this analogy in his private 1844 essay as too great a double coincidence (see Sutton 2014 for a deeper discussion) that Darwin could replicate both Matthew's unique hypothesis and his unique analogy to explain it, using trees, which were both the central topic of Matthew's book and his example in his original analogy.

The Man's Interference Analogy:

What did Matthew, Wallace and Darwin understand about artificial selection versus natural selection that makes the Artificial selection versus Natural Selection Analogy the perfect device to explain the natural process of selection?

An analogy is used as an explanatory device – a model.

An analogy is about what is analogous to what and why. In that way it must be kept simple. Simplicity is the most important criteria of a useful analogy – why else use one?

The next most important criteria of a good analogy is how close it is to reality (in my opinion). This is why the artificial selection analogy is so powerful, so useful.

Artificial selection is not natural selection, and so it is – like all analogies – a fallacy. But “selection” is the analogy. And it is close to reality as an analogy, because humans breed what they want into varieties they desire. Nature has no such cognitive purpose – selection in nature is born of random types being the most circumstance suited to survive and so they are better able to pass on their characteristics. But the outcome of this random generated process of natural selection leads to the most circumstance suited (in the wild) varieties – and, eventually, new species.

An analogy explains how two things are similar. What is similar in the case in point is “selection”. Selection is the only analogy. Selection is what is similar. Artificial selection by humans versus natural selection by nature. That is the analogy.Darwin, Wallace and Matthew all used it, and so did Low and Mudie.

Starting with the originator, Matthew, he Wallace and Darwin all understood that (1) a combination of artificial selection plus a necessary relaxation of natural selection leads, under human culture, to more varieties any one point in time kept within human culture. And (2) Natural selection often leads to fewer varieties at any one point in time in the wild, but those varieties can survive better under wild conditions than domesticated varieties – which most usually cannot. (3) Because in nature varieties come slowly to the fore that are more suited to survival in the wild than varieties selected relatively rapidly by human breeding programs, the analogy allows us to see that the process of natural selection is different to selection by humans. The natural process of selection is an unconscious and lengthy process leading to survival of the most circumstance suited. Humans are consciously selecting what suites immediate human needs and desires - even if that means those varieties need a greater deal of protection under human culture.

Test the hypothesis

Remember it is the 'Man's interference' explanatory analogy that we are looking for, not the full explanation of natural selection (although if you find that pre-1831 you will have stuck historical gold). Therefore, to dis-confirm the hypothesis we need to find evidence in the literature of others - pre-Matthew (1831) - realizing as a minimum that: (a) varieties consciously bred under human culture are less robust in the wild than naturally occurring wild varieties, because (b) in the wild, natural varieties must be most circumstance suited to wild conditions in order to survive and multiply. With that explanation in mind the essential hypothesis in question can be stated thus: (a) nature 'selects' varieties that are more suited to survival in the wild and that (b) distinct varieties bred by humans to suit human needs and desires are most usually less suited to the wild than natural wild species.

Other Darwinist Myths

1. Myths about Darwin (No 1.) The Darwin Archive Myth

2, Myths about Darwin (No 2.) The 'Galapagos Conception Myth' and 'Notebooks Myth'

No comments:

Post a Comment

Spam will be immediately deleted. Other comments warmly welcome.

On this blogsite you are free to write what you think in any way you wish to write it. However, please bear in mind it is a published public environment. Stalkers, Harassers and abusers who seek to hide behind pseudonyms may be exposed for who they actually are.

Anyone publishing threats, obscene comments or anything falling within the UK Anti-Harassment and the Obscene Communications Acts (which carry a maximum sentence of significant periods of imprisonment) should realize Google blogs capture the IP addresses of those who post comments. From there, it is a simple matter to know who you are, where you are commenting from, reveal your identity and inform the appropriate police services.